Website Homonymy in LLMs – A New Critical Challenge for SEO

“Sorry my friend, you’re mistaking me for someone else…” This is probably what your website would like to say each time an LLM confuses it with a more or less similar homonym. And it turns out that this situation occurs much more often than you might suspect…

To understand this, let’s take an example that will probably resonate with everyone. We all have that know-it-all cousin whose irritating erudition seasons family meals. His encyclopedic certainties, which he delivers in a peremptory tone, generally suffer no contradiction. It would be a shame to deprive yourself of the pleasure of trapping such an insufferable person. Ask this fool for information about the Bentley group and its website bentley.com: off he goes. He’ll overwhelm you with his inexhaustible knowledge about the prestigious British automobile brand, detailing with surgical precision the full-grain leather finishes, the W12 engine performance, and even the personal history of Walter Owen Bentley, without ever considering, even for a second, that it could be anything else. However, the domain name bentley.com belongs to Bentley Systems, a software engineering company that has absolutely nothing to do with luxury automobiles. Take that cousin !

Believe it or not, LLMs make exactly the same mistake as this unbearable cousin and associate the domain name bentley.com with the car brand. Welcome to the fascinating world of website homonymy in the LLM era, where the question “What does an LLM really know about mysite.com?” becomes existential. A world where these models, fed with billions of texts but lacking a structured knowledge graph, display their carelessness as soon as they are asked to be even slightly factual.

While traditional search engines have spent two decades refining their knowledge graphs to differentiate homonyms, LLMs continue to cheerfully mix up websites.

And that’s how we, SEO professionals, abruptly realize that all these years spent optimizing our title tags and meta descriptions might be useless against a system that mistakes the very respectable accounting firm “Martin & Associates” for a pet shop with the same name located on the other side of the country. What a disappointment!

In this article, we will explore this new frontier of search engine optimization, still little-known but now unavoidable. We will see why this identity confusion is not just an amusing anecdote, but a major issue for your visibility, your authority, and ultimately, your ability to exist digitally in a world where LLMs are gradually becoming the gatekeepers of access to information.

Fasten your seatbelts, the adventure promises to be as instructive as it is unsettling.

I. Understanding How LLMs Identify Websites

Mechanism for Processing URLs and Domains

Large language models process information fundamentally differently from search engines. Where Google has an organized index of web pages with precise metadata, LLMs work by recognizing textual patterns in their training corpus. Specifically, an LLM doesn’t have a database of websites, but simply statistical associations between sequences of tokens.

A domain name like “mysite.com” is therefore not a specific entry in an index, but rather a set of tokens that the model has encountered in its training data, associated with certain contexts or information.

The Fundamental Distinction: Recognition vs Understanding

There is a crucial difference between ecognizing the existence of a domain name (knowing that “mysite.com” is a website) and understanding the identity of this site (knowing what “mysite.com” is, its sector of activity, its content, etc.)

LLMs can easily recognize that a string of characters corresponds to a domain name, but their “understanding” of what this site represents depends entirely on the textual associations present in their training corpus.

The Limitations of Tokenization for Domain Names

The tokenization process of LLMs poses an additional challenge: depending on the models, a domain name can be split into several tokens, which complicates its precise identification. For example, “expert-accountant-london.com” could be tokenized into several fragments, making it more difficult for the model to maintain a coherent representation of this site as a single entity.

This technical fragmentation, combined with the absence of a formal system for identifying websites, explains why LLMs can easily confuse sites sharing similar names or dealing with related topics.

For those interested in a more in-depth analysis of the concept of homonymy in the broader sense as applied to LLMs, here is an academic article that seriously explores the subject.

These differences in approach translate very concretely into the way each system handles two entities that are nevertheless quite distinct.

II. Search Engines vs LLM: Two Models for Website Identification

How Search Engines Identify a Website

Search engines like Google have developed sophisticated systems to uniquely identify websites:

- Knowledge graphs: they associate a domain with a specific entity, with clearly defined attributes and relationships.

- Structured data: the implementation of Schema.org and other markup allows sites to explicitly specify their identity.

- Backlink analysis: the profile of incoming links helps to contextualize and qualify the site’s identity.

- User signals: user interactions with the site help refine its representation.

This multidimensional approach allows search engines to effectively disambiguate homonymous or similar sites and avoid confusion.

How LLMs “Understand” a Website

In contrast, current LLMs do not have a knowledge graph dedicated to websites. They rely entirely on textual mentions present in their training corpus and lack specific disambiguation mechanisms for domain names. This is why they easily confuse sites with similar names or evoking similar themes.

It seems they also rely heavily on backlinks pointing to your site. They could therefore extract some information from them, provided that their wording is not terse and that, on the contrary, it allows for contextualization. We are actively working to clarify this point.

This fundamental architectural difference explains why an LLM can attribute to your site characteristics that actually belong to a homonymous site, or vice versa.

Comparative Case Studies

Let’s take the example of two fictional sites: “centrale-assurance.com” (insurance broker) and “centrale-assurances.net” (blog about insurance).

In a search engine like Google, these two sites will be correctly distinguished thanks to their different backlink profiles, their structured data, and the analysis of their content. The engine understands that these are two distinct entities.

However, in an LLM, these two sites risk being confused. If a user asks “What services does centrale-assurance offer?”, the model might amalgamate information from both sites in its response, creating a hybrid and inaccurate representation.

New challenges bring new problems…

III. The Concrete Risks for Your Site’s Digital Identity

Identity Error

The first and most serious risk is total confusion between your site and a homonym. In this scenario, the LLM attributes to your site characteristics, content, or services that actually belong to another site with a similar name. This opens the door to all sorts of disasters: erroneous attribution of content or services, merging the identities of several sites into a single blurry entity, or associating your brand with information or qualities that don’t correspond to you.

For example, an accounting firm “Dupont Conseil” could see its website confused with that of a homonymous strategy consultant, leading to a completely erroneous representation of its services.

Dilution of Sectoral Expertise

If the LLM confuses your site with others in the same sector, it can attribute your specific expertise to competitors, weaken your distinctive positioning on topics where you are a leader, and dilute your authority by distributing it across several similar entities.

This thematic confusion is particularly harmful for sites whose value is based on pointed expertise or differentiating positioning.

Impact on Recommendation and Traffic

Identity confusion has direct consequences on traffic and conversions because LLMs can explicitly recommend competing sites thinking they’re talking about yours, users redirected to homonymous sites, and content attributions can benefit your competitors rather than you.

As LLMs become unavoidable intermediaries in accessing information, this confusion can therefore have a significant impact on your traffic acquisition.

IV. Aggravating Technical Factors to Monitor

Generic or Descriptive Domain Names: The Reversal of a Former SEO Advantage

Sites with generic or descriptive domain names are particularly vulnerable to identity confusion in LLMs. For example:

- “cheap-car-insurance.com”

- “best-plumber-new-york.com”

- “mortgage-loan-comparator.com”

From Traditional SEO to LLMs: The Turning of the Tide

For nearly two decades, using descriptive domain names containing strategic keywords was a recommended and effective SEO practice. This approach presented several advantages in the traditional search engine paradigm:

- Direct advantage in algorithms: historically, search engines gave significant weight to keywords present in the domain name

- Optimization of natural link anchors: links pointing to these sites naturally included target keywords

- Facilitated memorization: users more easily associated the site name with its function

This strategy remained generally positive, despite the evolution of algorithms. At least until the emergence of LLMs…

A Major Handicap in the AI Era

What was once an advantage is now transforming into a vulnerability:

- Dilution in generic concepts: descriptive names are frequently mentioned generically in training corpora, which dilutes the specific identity of the site in a broader concept.

- Multiplication of similar competitors: many sites have adopted similar names, creating sets of almost identical domains that LLMs struggle to differentiate.

- Confusion with queries: an LLM can confuse the domain name with a descriptive query, further drowning the site’s identity

For example, when a user asks for information about “mortgage-loan-comparator.com”, the LLM may interpret this as a generic request about mortgage loan comparators, rather than a query about this specific site. The model may then provide general information or mention several competing sites, completely dispersing the unique identity of the domain. It is likely that sites with descriptive domain names encounter more identity problems in LLM responses than sites with distinctive brand names.

Sites with Little Presence in the Training Corpus

Recent sites or those with a low presence in LLM training corpora are particularly exposed to the risk of confusion. Indeed, LLMs have fewer examples to understand the unique identity of these sites. Additionally, the lack of context promotes confusion with more established sites. Finally, the absence of qualified mentions makes it difficult to create an accurate representation.

This deficit of “contextualization” particularly affects new players and SMEs whose online presence is more limited.

Name Changes or Migrations

Sites that have changed names or migrated to a new domain face a particular challenge because LLMs often retain the old domain-identity association for a long time due to the temporal spacing of updates to their training data. In parallel, the temporary coexistence of both names creates lasting confusion. Moreover, updating the model’s knowledge depends on the integration of new information in future training data.

This inertia specific to LLMs can prolong identity confusion well beyond the period of technical transition. Not only are you facing a new problem, but it also risks proving stubborn…

V. Identity Hijacking: The Malicious Exploitation of Website Homonymy

Digital Identity Parasitism Strategies

Beyond natural confusion, some actors could deliberately exploit the weaknesses of LLMs to parasitize the identity of established sites, thus extending practices already well-known in the search engine universe. Indeed, the exploitation of homonymy and name similarities has existed since the beginnings of the web, but would take on a new dimension with LLMs through the acquisition of similar names (deliberate misspellings, TLD variations) to benefit from confusion, the evolution of old cybersquatting practices to specifically exploit confusion in LLMs, or the strategic reproduction of certain original content or elements.

While these techniques are reminiscent of those already used to deceive traditional search engines, they would potentially be more effective with LLMs due to their different understanding mechanisms and the absence of structured knowledge graphs.

These malicious practices would aim to intercept traffic or benefit from the reputation of an established brand without investing in its construction. So be vigilant and stay on the lookout!

Concrete Examples of Digital Identity Usurpation:

- The LinkedIn and LinkedUp case: In 2014, Microsoft sued the professional social network “LinkedUp” for trademark infringement, arguing that the name was deliberately chosen to create confusion with LinkedIn. This case perfectly illustrates how name proximity can be exploited to benefit from the notoriety of an established brand.

- Amazon and shops like “amazan”, “amaazon”, etc.: Many online shops have tried to exploit spelling variants close to Amazon, such as amazan.com, amaazon.com, or amazonn.net. Amazon has had to take legal action against several of these sites that used not only similar names, but also visual elements and site structures reminiscent of the original platform.

- Google and Googel: The site googel.com has long captured traffic intended for Google by exploiting a common typo. This “typosquatting” technique remains one of the most widespread forms of digital identity usurpation.

These examples, although dating from the pre-LLM era, show that the exploitation of homonymy is an established practice. With LLMs, this strategy could prove even more effective, as these models might have more difficulty distinguishing these similar entities than traditional search engines.

Impact on User Trust

These malicious practices would have consequences that would go beyond the direct victims, gradually eroding trust in the information provided by LLMs, which would lead to increased user distrust of site recommendations. The devaluation of authentic expertise in the face of multiplying usurpations could pose serious problems for web actors previously recognized as experts.

VI. Some Examples of Notable Confusions

The Emblematic Case of Bentley: Legitimate Homonymy Creating Confusion

As we mentioned in the introduction, a particularly revealing example of the challenges posed by homonymy concerns the Bentley brand. Contrary to what many of you might think, the bentley.com domain does not belong to the famous British luxury car manufacturer (Bentley Motors), but to Bentley Systems, an engineering software company specializing in infrastructure solutions. The car manufacturer had to settle for using bentleymotors.com as its main domain. What a blunder !

Screenshot of the bentley.com homepage

This situation is a textbook case for understanding the implications of LLMs in digital identity management:

- User confusion: The majority of users intuitively associate “Bentley” with luxury cars. If a user asks an LLM for information about “bentley.com”, without verification, the model might provide information about Bentley Systems (the legitimate domain owner) when the user expects information about the car manufacturer.

- Legitimate ambiguity vs. usurpation: Unlike cases of deliberate usurpation, this is a legitimate homonymy between two established companies in distinct sectors. The traditional legal framework doesn’t offer an obvious solution, since both entities have legitimate rights to the name “Bentley”.

- LLM responsibility: This case raises the question of LLMs’ responsibility in disambiguation. Should they try to clarify what the user is really looking for before providing an answer? How should they handle this ambiguity?

Other Emblematic Cases: Tesla and Nissan

Other notable examples illustrate these digital identity challenges:

Tesla and the late acquisition of its domain: For many years, Tesla Motors did not own tesla.com. Elon Musk’s famous company had to make do with teslamotors.com until 2016, when it finally managed to acquire the domain corresponding directly to its name. This temporary situation created potential confusion for nearly a decade, where users searching for Tesla on the web might not arrive at the car manufacturer’s official website.

Nissan.com and the legal battle: An even more striking case concerns nissan.com, which does not belong to the Japanese car manufacturer but to Uzi Nissan, an American entrepreneur who registered this domain in 1994 for his computer company, Nissan Computer. Despite years of legal battles, Nissan Motors has not managed to gain control of the domain and must settle for nissanusa.com for the American market. This situation has persisted for more than 25 years and represents an exemplary case of digital identity confusion, where the average user naturally associates “Nissan” with automobiles, but where the domain nissan.com leads to a completely different entity. Incredible !

Screenshot of the nissan.com homepage

These situations perfectly illustrate the challenges facing LLMs: how to correctly respond to a query about “nissan.com” without misleading the user, while respecting the reality of domain ownership?

This digital identity confusion, even in the absence of malicious intent, creates fertile ground for misunderstandings and problematic user experiences in interactions with LLMs.

You see how your online subsistence could be at stake ?

VII. Survival Kit to Strengthen Your Site’s Unique Identity

Implementation of Advanced Structured Data

Structured data plays a crucial role in strengthening the uniqueness of your website against LLMs:

- Complete implementation of Schema.org: use organization, website, and brand types to explicitly state your identity

- Consistent markup across the site: ensure systematic implementation across all pages

- Creation of connections between entities: establish clear links between your site, your organization, and your content

- Use of differentiation properties: use attributes like “sameAs” to link your site to your official presences on other platforms

This approach contributes to creating an internal knowledge graph that facilitates the unique identification of your site.

Development of a Distinctive Lexical Footprint

Creating a recognizable linguistic signature strengthens your site’s unique identity. Adopt vocabulary specific to your brand, use recognizable turns of phrase in your content, maintain a distinctive editorial voice by using notably redundant formulations so that they become your signature.

This distinctive lexical footprint facilitates the differentiation of your site in the vector representations of LLMs.

Creation of Specific Self-Identification Content

Develop content explicitly dedicated to clarifying the unique identity of your site, with particular attention to your “About” page which plays a crucial role in this context.

The “About” Page: Cornerstone of Your Digital Identity

Long disdained, the “About” page (or “Who We Are”) is a factor of identity differentiation against LLMs, far beyond its traditional role as a self-centered showcase. Yet, LLMs often give significant weight to this page when forming their representations of a website. It is generally considered an authoritative and trustworthy declaration of identity, particularly because it brings together key elements that LLMs use to contextualize a site: history, mission, team, positioning, differentiators. Moreover, it’s the ideal place to clear up any potential ambiguity about your identity, particularly in cases of known homonymy. To go further, here’s our detailed methodology on optimizing the “About” page

VIII. Measuring and Optimizing Your Differentiation Strategy

Waikay.io, a tool that meets the challenge

Fortunately, the heavens are on your side. Our waikay.io tool allows you to check exactly what LLMs know about your website and gives you keys to solve problems. If by misfortune there were any… which we don’t doubt.

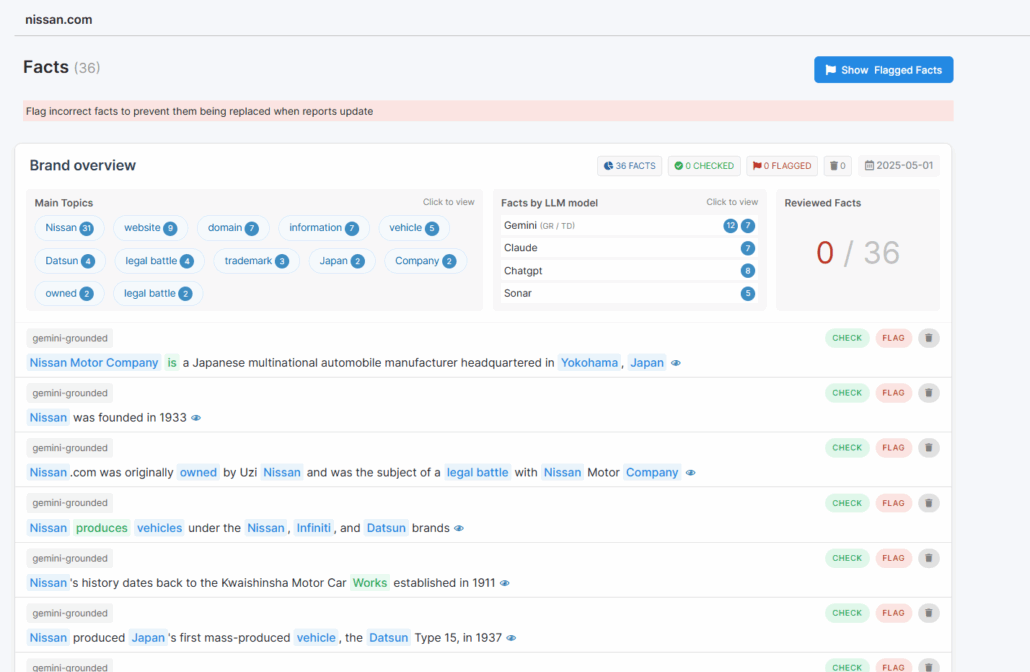

Waikay allows you to create a report around your brand by inputting your full domain name and filtering through facts it reports about you by different llms. Let’s take a look at nissan.com, the aforementioned memorial page.

Waikay prompts chatgpt, gemini, sonar and claude to provide ai overviews of this website. It will then curate a list of facts that are reported which can be flagged and monitored over time. In this special cae, all LLMs have reported the wrong facts, even though we gave a direct webiste access. It highlights the AI’s mixed understanding of websites and allows you to go through everytging with a fine tooth comb when it comes to your online narrative.

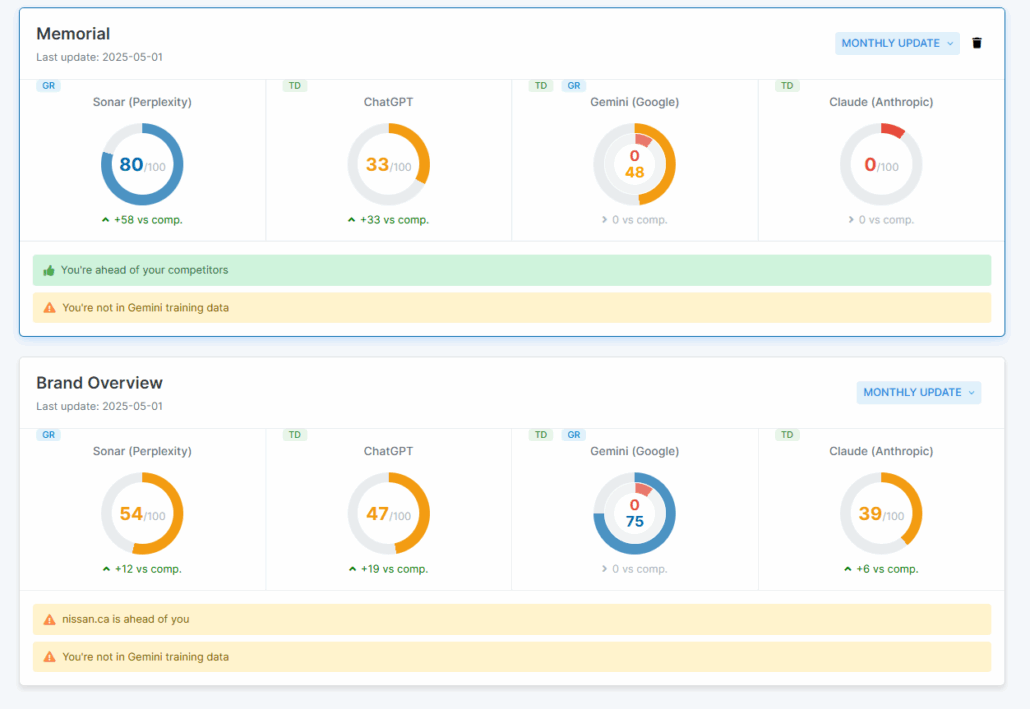

Furthermore, you can start to add some context to these facts. You can create seperate projects for entities associated with your website. For example, if we want to look at nissan.com in the context of ‘memorial’, the facts suddenly become slightly more relavant.

In this way we can really montor not just the insane hold the brand salience of nissan the car company has over ai, but also which llms are more adaptable to new information. Sonar and gemini seem to come out on top here in the knowledge race, so either nissan (the car company) or nissan (the memorial site) can measure the way AI understands the dispute.

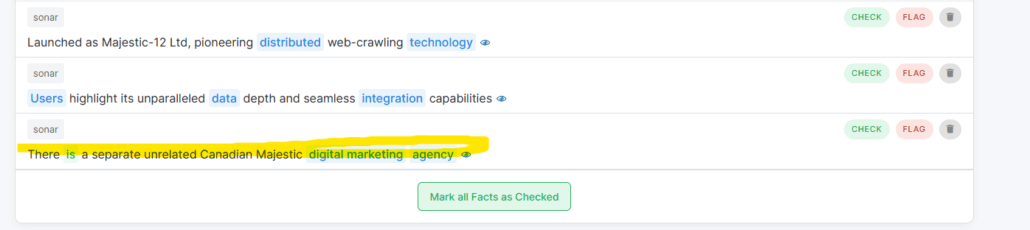

An interesting, and slightly more SEO based, case to look at could be Majestic.com. This is a brand with tonnes of authority and clearly defined online presence should’t run into any confusion. However, it’s great to check with waikay whether brand homonyms are infiltrating the space. Majestic.com refers to the seo brand, and majestic.co.uk refers to the wine company. Interestingly, neither of these were brought up in the ai overview, but the canadian agency majestic was (choutout canadianmajestic!).

And just like that you can find where you may be falling victim to brand homonymy with waikay! It’s great to keep on top of this to ensure you online narrative ins’t being skewed by other brands, and it is a fabulous and thorough way to track this.

If things do turn out to be skewed, I would reccomend taking a look at the sources that waikay provides. Skewed narrative can often be from third party review sites, so head over to the mentions tab and look at the ‘unique domains’ to find some of the more… niche… sites that AI is pulling your data from.

Manual Testing Methodologies with LLMs

Beyond specialized tools, several approaches allow you to evaluate the recognition of your site by LLMs:

- Tests through prompt engineering: develop series of targeted questions to assess the accuracy of LLMs’ knowledge about your site:

- Direct recognition:

- “What is [yoursite.com]?”

- “What is the business sector of [yoursite.com]?”

- Simple confusion:

- “What is the difference between [yoursite.com] and [homonymous-competitor.com]?”

- Attribution:

- “Who developed/created [product or service specific to your company]?”

- Context:

- “I’m looking for [service you offer] in [your location]. Which sites do you recommend?”

- Disambiguation:

- “I’m confused between several companies named [your name]. Can you help me distinguish them?”

- Conversational memory:

- Start by mentioning a homonymous competitor and then ask for information about “this company” without naming it again

- Direct recognition:

- Comparative tests: analyze how LLMs distinguish (or confuse) your site with similar domains

- Generated content analysis: evaluate how your site is represented in sector summaries or thematic recommendations

Of course, these tests must be performed with a rigorous scoring method (scale of 1-10) to objectively measure the level of confusion. Are we professionals or not?

These complementary methods are certainly time-consuming but allow for a qualitative evaluation of your site’s representation in LLMs. That said, nothing beats the execution speed and almost immediate comprehensiveness of our tool…

Conclusion

Here we are at the dawn of a new era of SEO, where after spending years worrying about what Google thinks of us, we must now worry about what language models know about us.

The problem of website homonymy in LLMs is not just a technical curiosity reserved for geeks. It’s a major issue that could well transform your laborious SEO work into a sandcastle at high tide. After all, what’s the point of being first on Google if Claude or ChatGPT systematically confuses you with a culinary site, or worse, a pornographic one?

SEO professionals are therefore facing a new challenge: not only do they have to please Google’s algorithm, but they now also have to ensure that LLMs don’t suffer from an advanced form of digital prosopagnosia, always a good word to use, when it comes to your website. A task all the more complex because these models function like impenetrable black boxes, whose confusions can only be corrected indirectly and with a latency measured in model versions rather than days.

So what to do? Probably start by taking this issue seriously before your CEO discovers that according to ChatGPT, your cybersecurity company actually offers “excellent discounted Nile cruises.” It will put you in a better position than your competitors who continue to ignore this new SEO territory.

And who knows? Maybe one day,” I had a dream”, LLMs will develop enough discernment to distinguish your architectural firm “Perspective Design” from a blog about optical illusions squatting on perspective-design.net. Until then, consider homonymy as the new playground (or rather battlefield) of modern search engine optimization.

As a Greek philosopher whose name I’ve forgotten said: “To be confused or not to be referenced is strictly the same thing.” Or something like that.